We advance research and discovery in biology — from molecules to the global biosphere, from cells to human communities, across time and space.

Whether it’s studying how wildlife diversity affects human health or how memory is encoded in the brain, NSF research helps the world understand the rules that govern life and sustain the complex web of living things.

What we support

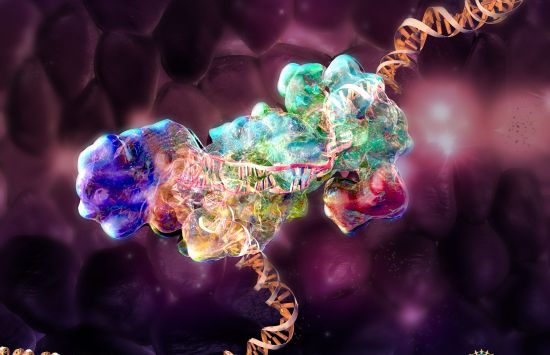

Deciphering the molecular underpinnings of life

We support research that uncovers the fundamental and emergent properties of living systems, from atoms and molecules to cells.

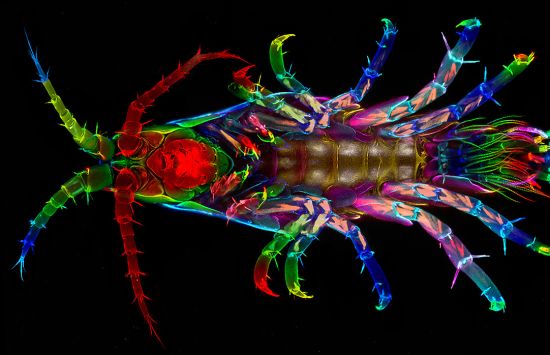

Understanding the structure and function of organisms

We support research aimed at understanding organisms as units of biological organization.

Exploring the ecology and evolution of living things

We support evolutionary and ecological research on species, populations, communities and ecosystems.

Investing in research infrastructure

We support the development and enhancement of biological research infrastructure, including human capital, technologies, and institutes and centers.

Expanding the frontiers of 21st century biology

We support multi- and interdisciplinary research and networking activities that arise from advances in disciplinary research.

Visit the Emerging Frontiers Office

Learn about NSF's support for research on biotechnology and artificial intelligence.

Addressing societal challenges

We invest in NSF-wide research themes that are designed to address societal challenges, including climate change. Many advances in these areas also involve development of innovative biotechnology. These topics can be explored in the related topics section of this page.

Featured news

Educational resources

View lesson plans, activities and multimedia for K–12 audiences that focus on explorations of living things.

View the resources