The bubble-bursting, causality-revealing awesomeness of randomized controlled trials

Countless lives have been helped or saved with the scientific evidence provided by an experimental approach three economists unleashed more than 20 years ago. Their innovation gave rise to a scientific movement that is clearly illuminating causality — how one thing directly causes another — within the intricate chaos of human behavior and society.

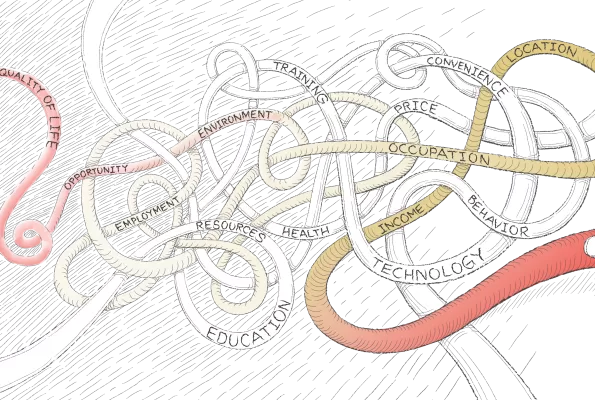

What are the most efficient ways to change the world for the better? What actions will effectively reduce poverty and illness, minimize violent crime or strengthen community resilience to extreme weather? Many governments and philanthropic organizations in the U.S. and abroad grapple with those tough questions when deciding how best to use the limited resources entrusted to them by taxpayers or donors.

Answering such complex questions requires clearly seeing something that is all too often hidden or murky: causality. Did a particular policy or initiative actually cause the desired effect? Or was it just a coincidence?

In the 1990s, a small group of researchers developed a scientifically rigorous way to design complex social experiments that can clearly distinguish those all-important causes from mere correlations and coincidences. Their method recast a statistical technique traditionally used in clinical medical trials, giving rise to a new movement in social science research and winning them a Nobel Prize.

Appropriately referred to as "the gold standard" for its highly valued ability to unmask the hidden nature of human behavior and society, its actual name is mundane: the randomized controlled trial, or RCT for short.

Over more than 20 years, RCTs have been used again and again in social experiments to slice through misconceptions, dispel vagaries and provide the evidence needed to implement policies and interventions that have saved millions of lives and improved the quality of life for countless more.

An indispensable tool

"The RCT allows you to train your light wherever you want it trained," says Esther Duflo, one of the economics researchers who first used randomized controlled trials in social experiments. Her research illuminated the real-world effects of micro-loans and other strategies intended to alleviate poverty.

Duflo and her colleagues Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer were awarded the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for their pioneering work studying causes and effects related to poverty and education, and in the process forging an indispensable tool for social science research. The U.S. National Science Foundation invested in the work of all three researchers.

"It's turned out to be much more versatile than I would have anticipated," says Kremer of the many puzzles researchers have cracked using RCTs over the last three decades. Kremer was arguably the first researcher to conduct an RCT as a social experiment when he studied the effects of providing textbooks and other educational interventions for schoolchildren in Kenya in the mid-1990s. The results showed that providing textbooks alone did not raise average test scores, upending existing theories about education at the time.

At the heart of every evidence-yielding RCT is a painstakingly designed experiment that isolates the effects of a particular variable, or intervention, from the legion of other things that can influence human behavior. Researchers must identify participants — sometimes tens of thousands of them — who are similar to each other in age, health, living environment or other factors depending on the intervention being tested.

Researchers then randomly select some participants to become the variable group (those that receive the intervention) and others to become the control group (those that do not). The researchers then must carefully track every participant and compare them, sometimes for years, to separate causation from correlation and thus reveal the true impact of the intervention.

It's a time-consuming and difficult process. But, similar to high-precision atomic clocks, gene sequencing machines and other once exotic scientific instruments, RCTs are now a fairly commonplace tool embraced by researchers and professionals seeking to understand human behavior and society.

"I think they're useful in a deeper way than we first realized," reflects Kremer. "You need to use the right tool for the right purpose, but it turns out that RCTs are useful for a lot of things."

These uses include understanding how to reduce violent crime in our communities, provide more kids with a full belly of food every day or improve the effectiveness of healthcare messaging. RCT-wielding researchers are conducting experiments that clearly reveal what works and what doesn’t for a wide range of social challenges.

In 2003, Duflo, Banerjee and Sendhil Mullainathan founded the Poverty Action Lab at MIT to focus on reducing poverty by ensuring that relevant policy is informed by scientific evidence. Now named the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, or J-PAL, the lab and its affiliates have conducted over 1000 RCTs.

“More policies are based on good evidence than before,” says Duflo of the impact that RCT-fueled research has had on a national and international scale. “We can point to a number of cases where having the evidence changed the policy discourse.”

Among those many cases is one concerning the fight against a deadly disease, the insect that spreads it and a misconception about how much a simple but life-saving item should cost.

Give it away

Malaria has been described as causing a pain so intense it feels like you're being repeatedly shocked by a taser. According to the CDC, more than 600,000 people died from Malaria in 2020 alone. Most were young children in sub-Saharan African countries where basic medical services and medicines are sparse or unavailable. In such areas, preventing the most common source of malaria infection — mosquito bites — is essential.

For decades, there has been a simple, cheap and highly effective preventative measure for malaria: draping insecticide-treated mosquito nets over beds, cribs and any other place where adults or children sleep. In the past, however, many researchers and policymakers believed that people would not reliably use mosquito nets provided at no cost because they wouldn't value them.

"The dominant narrative was that they needed to be sold, not given away, because people would not use them properly if they had not paid for it," explains Duflo.

Thus, philanthropic and government organizations who distribute vast numbers of lifesaving nets usually charged a price, even though the people who need the nets most are very poor and sometimes cannot afford them. This seemingly paradoxical idea was genuinely thought to be the best way to save the most lives.

That idea, as it turned out, was wrong.

In 2006, J-PAL conducted a series of extensive RCTs in eight countries showing the effects of providing mosquito nets at different prices. Their carefully designed experiments repeatedly revealed that people will reliably use the nets regardless of whether they paid anything for them. And people who received a net for free were more likely to purchase nets in the future.

"That work really changed people's minds," says Duflo. "Nets have now been massively provided for free, which was responsible for a huge decline in malaria cases."

In addition to disease prevention, Duflo and her J-PAL colleagues have conducted RCTs exploring agriculture, violence and crime, finance, nutrition and more. "In J-PAL we maintain a count of the number of people touched by policies that anybody in our network found to be effective," she adds. "It's about half a billion."

The 'randomista' movement

Out on the endless frontiers of science, researchers in an increasingly diverse number of fields are training the sharp light of RCTs on a host of critical and complicated issues.

During the COVID-19 pandemic alone, multiple experiments using RCTs exposed the behavioral effects of public health practices that were previously hidden or just guessed at. For example, health-related messages delivered by doctors and nurses on social media are persuasive and changing the questions asked during contact tracing interviews can yield far more effective results.

"A big part of what researchers do is innovation," says Kremer. "Randomized trials and the experimental approach really help with that. We're trying new things and that, I think, is directly productive for society."

The innovation that Duflo, Banerjee and Kremer helped unleash decades ago has indeed grown in all sorts of directions as the science and engineering community has increasingly found original ways to put RCTs to valuable new uses.

For example, a group of engineers teamed up with developmental psychologists and others to conduct an RCT exploring the effects of using robots to help children with autism spectrum disorder. Another project is using an RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to help people and local communities recover from the opioid crisis. A third is testing changes to the assignment transfer process in the U.S. Army to explore the potential benefits for officer retention and performance in the military. Yet another RCT was conducted by computer scientists to explore the impact of using different computer languages on the efficiency and productivity of programmers. The list goes on.

The clarity yielded by RCTs does not come easy, though. "Randomized controlled trials are hard to run because you have to make many decisions — usually at a fast pace — and those decisions have consequences," says Duflo. "You think of these decisions as a scientist but take them at speed as a firefighter."

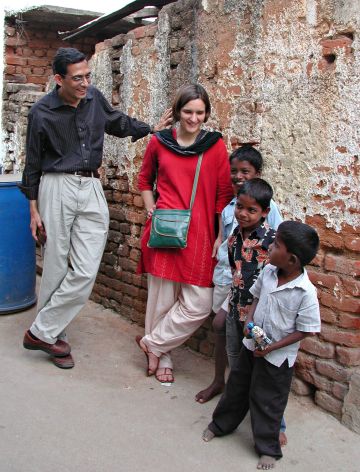

The oftentimes difficult process of conducting an RCT has the side benefit of bringing researchers out of the proverbial ivory tower and onto the ground, working directly with people, says Kremer. "If you're trying to study agricultural extension or loans to small farmers, well, you spend time with farmers or small business owners and that brings you much closer to reality."

"What we were told when we got the Nobel Prize is that we started a movement," recalls Duflo. Empowering the "randomista" movement and all the valuable results and discoveries that other researchers continue to achieve is what Duflo is most proud of.

And what big, unsolved problems might inventive scientists crack with RCTs in the future? Duflo won't speculate on that.

"The most important answer to this question is that I don't want to be the person who answers this question," she says. "I want it to be answered by the community of researchers."