News Release 12-214

Microbial "Missing Link" Discovered After Man Impales Hand on Tree Branch

Scientists uncover how insects domesticate bacteria

A homeowner cutting down a crab apple tree led to a new, far-reaching scientific finding.

November 15, 2012

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

It all started with a crab apple tree.

Two years ago, a 71-year-old Indiana man impaled his hand on a branch after cutting down a dead tree. The wound caused an infection that led scientists to discover a new bacterium and solve a mystery about how bacteria came to live inside insects.

On Oct. 15, 2010, Thomas Fritz, a retired inventor, engineer and volunteer firefighter, cut down a dead, 10-foot-tall crab apple tree outside his home near Evansville, Ind.

As he dragged away the debris, he got tangled in it and fell. A small branch impaled his right hand in the fleshy web between the thumb and index finger.

A former emergency medical technician, Fritz dressed the wound, which became swollen. Then he waited for a scheduled visit with his doctor a few days later. By then, a cyst formed at the wound site. The doctor put Fritz on an antibiotic after sending a sample of the cyst to a lab.

The pain and swelling persisted and the wound became abscessed.

About five weeks after the accident, an orthopedic surgeon removed several pieces of bark from the wound, which finally healed without further incident.

Only later did Fritz find out that his infected wound contained a previously unknown bacterium that scientists say could be used to block disease transmission by insects and prevent crop damage.

Scientists call the new strain human Sodalis or HS; it's related to Sodalis, a genus of bacteria that lives symbiotically inside insects' guts.

The journal PLOS Genetics published a paper detailing the discovery today.

"Symbiotic interactions between microorganisms and insects are common, and biologists suspect that they're an important driver of biological diversification," says Matt Kane, program director in the National Science Foundation's Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research.

"But how such symbioses came to be is often a mystery," Kane says. "This particular story has a happy ending, but also an interesting one, because researchers used it to gain insight into how insects and microbes can form symbiotic partnerships in the first place."

As in the case of the crab apple tree, "there are bacteria in the environment that form symbiotic relationships with insects," says University of Utah biologist Kelly Oakeson, the study's lead co-author. "This is the first time such a bacterium has been found and studied."

Identifying a New Strain of Bacteria

The lab that first received the sample from Fritz's infected wound couldn't identify the bacterium once it was isolated. So the organism was shipped to ARUP Laboratories, a national pathology reference library operated by the University of Utah.

An automated analysis at ARUP found that the bacterium from Fritz was E. coli, but scientists doubted the results.

"We had close matches for it, but none were validly described species," says Mark Fisher of the ARUP Institute for Clinical and Experimental Pathology and a co-author of the paper. "It caught my eye because I knew Colin Dale worked on Sodalis."

Dale is the researcher who discovered and named Sodalis in 1999. He is a biologist at the University of Utah and is the study's senior author.

He says that genetic sequencing showed that the HS bacterium is related to bacteria that live symbiotically in 17 insect species, including tsetse flies, weevils, bird lice and stinkbugs, and is most closely related to bacteria in the chestnut weevil and a stinkbug species.

The study compared HS with genomes of the strain Sodalis glossinidius that lives in tsetse flies and another Sodalis-like bacterium that lives in grain weevils.

Compared with HS, the other two bacterial species have lost or deactivated about half their genes.

A Missing Link

According to Dale, the findings provide "a missing link in our understanding of how beneficial insect-bacteria relationships originate.

"They show that these relationships arise independently in each insect. The insect picks up a pathogen that is widespread in the environment and then domesticates it. This happens independently in each insect."

A competing theory is that parasitic wasps and mites spread symbiotic bacteria from one insect to another.

Dale says that theory cannot explain why such similar types of Sodalis bacteria are found in insects that differ widely in location and diet, including insects that feed either on plants or animals.

The new results support the theory that insects are infected by pathogenic bacteria from plants or animals in their environment, and that the bacteria evolve to become less virulent and to provide benefits to the insect.

Then, instead of spreading from one insect to another, the bacteria spread from mother insects to their offspring.

Taming Invading Bacteria

Various bacteria live symbiotically in blood or fat cells or in special structures attached to the guts of as many as 10 percent of all insects.

The bacteria gain shelter and nutrition from their insect hosts, and they produce nutrients--B vitamins and amino acids--to help feed the insects.

Sometimes they also produce toxins to kill invaders, such as fungi or the eggs laid in an insect by a parasitic wasp.

Sodalis is only one of several types of bacteria that live in insects.

Symbiotic bacteria are known for having the smallest genetic blueprints, or genomes, of any cellular organism because as they evolve inside an insect, they lose genes that would be needed for survival outside the insect.

But when biologists sequenced the new bacterium's genome, they found that HS has a relatively large genetic blueprint and is closely related to Sodalis-like bacteria that have smaller genomes and live in many species of insects, implying that Sodalis-like bacteria all descended from a bacterium like HS.

A Way to Block Some Insect-Spread Diseases?

The researchers believe the discovery could have important implications. They say it may be possible to genetically alter the new bacterium to block disease transmission by insects like tsetse flies and prevent crop damage by insect-borne viruses.

"If we can genetically modify a bacterium that could be put back into insects, it could be used as a way to combat diseases transmitted by those insects," says Adam Clayton, a University of Utah biologist and lead author of the paper unveiling the new bacterium and its genome.

Tsetse flies and aphids both carry symbiotic Sodalis bacteria related to strain HS. Sodalis doesn't grow well outside insects, but HS grows well in the lab.

So it may be possible to insert genes in HS, and then place the bacteria in tsetse flies to kill the protozoan parasites that live in the flies and cause sleeping sickness in people and domestic animals in Africa.

Aphids transmit many plant viruses that attack soybeans, alfalfa, beets, beans and peanuts.

Replacing their normal symbiotic bacteria with a genetically engineered strain of HS could interfere with disease transmission.

The researchers speculate that in addition to the HS bacterium, there are likely many other undiscovered bacteria in the environment that could form symbiotic relationships with insects.

"We have identified very few of the bacteria that exist in nature," says Dale, "and new species and strains like HS are often only discovered when they infect humans."

Additional co-authors of the paper are Maria Gutin, Arthur Pontes, Diane Dunn, Andrew von Niederhausern and Robert Weiss, all of the University of Utah.

The National Institutes of Health also funded the research.

-NSF-

-

After being impaled by part of a crab apple tree, the wounded homeowner sought help.

Credit and Larger Version -

Biologist Colin Dale swabs a petri dish that has a bacterial culture from the man's wound.

Credit and Larger Version -

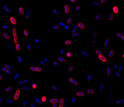

Microscopic image showing newly discovered bacterial strain; cell walls are red, DNA is blue.

Credit and Larger Version -

The new bacteria are related to those that live inside insects called grain weevils.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

Lee Siegel, University of Utah, (801) 581-8993, email: lee.siegel@utah.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov