Multimedia Gallery

Molecular Rotor/motor Project (Image 3)

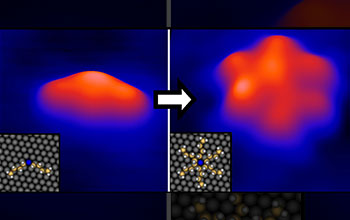

Pictured here is a stationary (left) versus a spinning (right) rotor molecule. At very low temperatures (close to absolute zero) it is possible to stop the rotation of molecules because the molecules do not have enough energy to spin. Energy applied to the stationary molecule in the form of heat or electrical current can induce rotation. When supplied with energy, the molecule will spin around a central axle, similar to a propeller. In the bottom-left corner of each image are schematics. In this schematic, blue=sulfur, yellow=carbon, white=hydrogen and gray=gold atoms.

This research, supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (CHE 08-44343), was conducted in the lab of Professor E. Charles H. Sykes in the chemistry department at Tufts University. For further information about this research, including a video, visit http://ase.tufts.edu/chemistry/sykes/Sykes%20Lab%20Research%20Group.html.

More About This Image

As devices become smaller and smaller, moving parts are needed on a more miniature (nano) size scale. One such component that will be required to build nanoscale machines is the rotor. Just as gears and ratchets are used in everyday life to produce motion, making nanoscale counterparts will be a crucial step towards building tiny machines out of molecules. These nanomachines can be found throughout our bodies in the form of proteins, which complete tasks such as cellular motion or muscle contraction. However, very little is known about how to harness the motion of individual molecules in order to perform similar tasks.

Professor Sykes has found a group of molecules with which to study the basic properties and mechanics of rotation. In order to turn a rotor into a useful machine, Sykes' group will need to be able to use a fuel source to drive mechanical motion. Their molecular rotors can be spun using heat or an electrical current as the fuel. While heat provides an easy source of energy, rotation by this method is random and uncontrollable. However, recently Sykes found that by exciting vibrations of the chemical bonds between individual atoms, it is possible to rotate molecules on command. This capability will make the complicated task of powering nanomachines much easier for future studies of directed motion. (Date of Image: 2007-2009) [Image 3 of 4 related images. See Image 4.]

Credit: Heather L. Tierney, April D. Jewell and E. Charles H. Sykes, Chemistry Department, Tufts University

Images and other media in the National Science Foundation Multimedia Gallery are available for use in print and electronic material by NSF employees, members of the media, university staff, teachers and the general public. All media in the gallery are intended for personal, educational and nonprofit/non-commercial use only.

Images credited to the National Science Foundation, a federal agency, are in the public domain. The images were created by employees of the United States Government as part of their official duties or prepared by contractors as "works for hire" for NSF. You may freely use NSF-credited images and, at your discretion, credit NSF with a "Courtesy: National Science Foundation" notation.

Additional information about general usage can be found in Conditions.

Also Available:

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (1 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.