Found in space: Complex carbon-based molecules

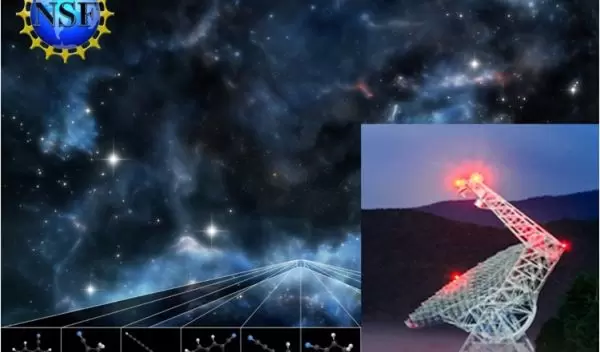

Much of the carbon in space is believed to exist in the form of large molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs. Since the 1980s, evidence has indicated that these molecules are abundant in space, but they have not been directly observed. Now, a team of U.S. National Science Foundation-funded researchers led by Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientist Brett McGuire has identified two distinctive PAHs in a patch of space called the Taurus Molecular Cloud.

PAHs were believed to form efficiently only at high temperatures -- on Earth, they occur as by-products of burning fossil fuels, and are found in char marks on grilled food. The Taurus Molecular Cloud has not yet started forming stars, however, and its temperature is about 10 degrees above absolute zero.

This discovery suggests that these molecules can form at much lower temperatures than expected, and it may lead scientists to rethink their assumptions about the role of PAH chemistry in the formation of stars and planets.

"What makes the detection so important is that not only have we confirmed a hypothesis that has been 30 years in the making, but now we can look at all the other molecules in this one source and ask how they are reacting to form the PAHs we're seeing, how the PAHs may react with other things to possibly form larger molecules, and what implications that may have for our understanding of the role of very large carbon molecules in forming planets and stars," says McGuire, who is a senior author of the new study, which appears in Science.

Carbon plays a critical role in the formation of planets, so the suggestion that PAHs might be present even in starless, cold regions of space may prompt scientists to rethink their theories of what chemicals are available during planet formation. As PAHs react with other molecules, they may start to form interstellar dust grains, the seeds of asteroids and planets.

"We need to entirely rethink our models of how the chemistry is evolving, starting from starless cores, to include the fact that they are forming these large aromatic molecules," McGuire says.

Adds Glen Langston, a program director in NSF's Division of Astronomical Sciences, "In an excellent example of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and basic science, these researchers cleverly applied data stacking techniques from the fields of astronomy, chemistry and data science that were developed at the NSF's Green Bank Telescope."