How 'Iron Man' bacteria could help protect the environment

Researchers at Michigan State University have shown that microbes are capable of a feat that could help reclaim a valuable natural resource and soak up toxic pollutants.

The U.S. National Science Foundation-funded team published its discovery in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology.

Geobiologist Gemma Reguera works with bacteria known as Geobacter, found in soil and sediment. She investigated what happens to the bacteria when they encounter cobalt.

Cobalt is a valuable but increasingly scarce metal used in batteries for electric vehicles and alloys for spacecraft. It's also toxic to living things, including humans and bacteria.

"It kills a lot of microbes," Reguera said. "Cobalt penetrates their cells and wreaks havoc."

But the team suspected Geobacter might be able to escape that fate. The microbes are a hardy bunch. They can block uranium contaminants from groundwater and can power themselves by pulling energy from minerals containing iron oxide.

Scientists know little about how microbes interact with cobalt, but many researchers believed the toxic metal would be too much for the microbes.

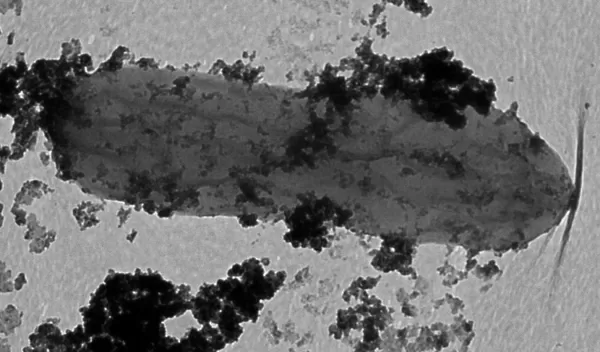

Reguera's team challenged that thinking and found Geobacter to be effective cobalt "miners," extracting the metal from rust without letting it penetrate their cells and kill them. Rather, the bacteria essentially coat themselves with the metal.

"They form cobalt nanoparticles on their surface and metallize themselves with a shield that protects them," Reguera said. "It's like 'Iron Man' when he puts on his suit."

Reguera sees this discovery as a proof-of-concept that opens the door to exciting possibilities. For example, Geobacter could form the basis of new biotechnology to reclaim and recycle cobalt from lithium-ion batteries, reducing the nation's dependence on foreign cobalt mines.

The discovery also invites researchers to study Geobacter as a means of soaking up other toxic metals that were believed to be death sentences. Reguera is particularly interested in seeing if Geobacter could help clean up cadmium, a metal found in industrial pollution.

"This novel research may lead to possible applications with both environmental and economic benefits, such as improving domestic supplies of cobalt, a critical metal," said Enriqueta Barrera, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences.