Dust in the wind: North Pacific Ocean fertilized by iron in Asian dust

Vast subtropical gyres -- large systems of rotating currents in the middle of the oceans -- cover 40% of the Earth. The gyres have long been considered biological deserts, with waters that contain very few nutrients to sustain life.

The regions are also thought to be remarkably stable, yet scientists have documented an anomaly in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre ecosystem that has puzzled oceanographers. The region's chemistry changes periodically, especially its levels of phosphorous and iron, ultimately affecting its biological productivity.

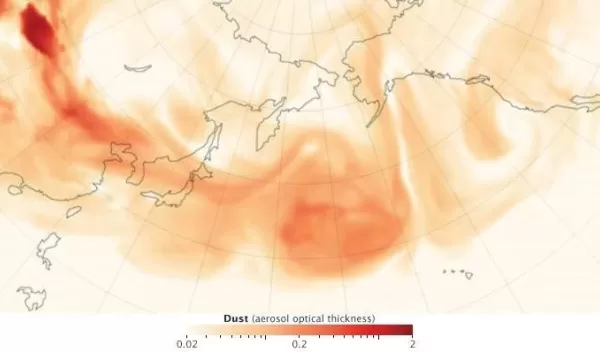

In a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers document what leads to the variations: changes in the amount of iron that's deposited into the ocean by wind-borne dust from Asia.

"We now know that these areas, once thought to be barren and stable, are actually quite dynamic," said Ricardo Letelier, an Oregon State University biogeochemist and ecologist who, in collaboration with scientist David Karl at the University of Hawaii, led the study.

The research focused on the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre and used data from Station ALOHA's Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOTS) program.

"Scientists drew on more than three decades of HOTS data to expand our understanding of how dust controls productivity in a vast region of the North Pacific," said David Garrison, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research. "These results demonstrate the value of long-term research."

The surface layer of the North Pacific gyre has very clear waters with hardly any nutrients. The extraordinary clarity of these waters allows sunlight to penetrate deep into the water column and support photosynthesis below 100 meters (328 feet).

The researchers noticed that the levels of phosphorous and iron, nutrients important for life, changed significantly in North Pacific gyre surface waters during the three decades of the study.

The team linked these changes with iron input from Asian dust. A combination of factors is at play: desertification of the Asian continent, which allows more dust to be carried on the wind; combustion, especially from wildfires; factory outputs; and wind patterns across the North Pacific Ocean.