Building a Machine to Search for Cosmic Secrets

Early on the morning of Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2008, the cold, wet wind was enough to shock me awake as I arrived at the surface assembly building above the cavern of the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment, a subatomic particle detector that is a key component in the subterranean Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that straddles the French and Swiss borders.

One of the largest international scientific collaborations to date, the LHC is an underground ring, 27 kilometers (16.7 miles) around, located at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland.

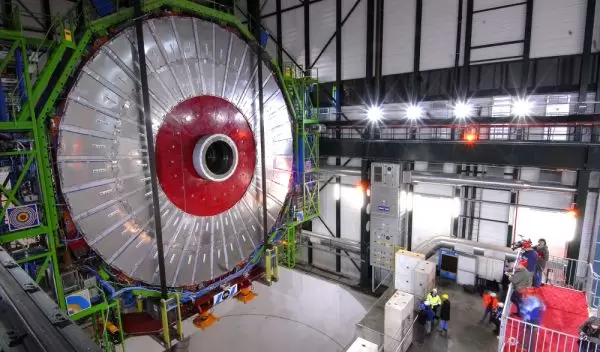

The 6 a.m. gathering included three film crews, several photographers and head honchos of the engineering and technical coordination staff. We stood with eyes and cameras trained on the concrete door in the floor,1.8 meters (6 feet ) thick with sides 20.4 meters (67 feet) long, that slid out from under the 1,430-ton slice of the detector.

The slice was already suspended by 220 cables coming from a gantry crane rented from VSL Heavy Lifting, a company also commissioned to lift ships into dry docks. The crane works through "grasp-release" operations, in which one winch clamps down on the cables while another moves back, "hand over hand, like paying out rope on a sailing boat," explained technical coordinator Austin Ball.

As the red and silver medallion sank slowly below the floor of the building, the warehouse seemed an empty shell--the last of the detector slices was leaving the building where it was assembled for the cavern in which it will help reveal secrets of the universe. By examining the uncommon particles that the LHC will produce in proton collisions, CMS researchers hope to open a window on ideas such as extra dimensions, dark matter and supersymmetry.

The technical staff, with 14 successful lowerings under their belts, seemed almost ho-hum about the day's procedure. They were in for a couple of surprises, however. When the slice drew to a halt around 7:45 a.m., I sidled up to Ball for an explanation. One of the cables was caught in its winch.

"It's not completely unexpected," said Ball, unperturbed. "Statistically, this should happen once in about 5,000 of these grasp-release operations." Senior engineer Hubert Gerwig estimates that the clamps had tightened on the cables approximately 6,000 times over the course of lowering the fifteen detector slices.

Although the crews were concerned that the cable might be broken, it quickly became clear that the cable had merely unraveled a bit. The lowering technicians disengaged the cable until the damaged part was past the winch.

The wind, on the other hand, posed a problem that the engineers and technicians could not address. There were gusts as high as 97 kilometers (60 miles) per hour during the night. Some worried that the wind could cause vibrations in the lowering gear, possibly driving the slice to swing like an enormous pendulum. The team was unwilling to take the risk, having a scant 7 centimeters (3 inches) to spare on either side, once the slice reached the cavern.

Luckily, the wind fell to 48 kilometers (30 miles) per hour, and the lowering resumed as soon as the cable was fixed. The wind never got above half the speed that the gantry crane was prepared to handle, Gerwig asserted. "There was no problem for the structure."

When the last piece of the detector gently touched the floor of the CMS cavern at around 5:30 that evening, a round of applause sounded from the scaffoldings. CERN's Director General Robert Aymar and CMS spokesperson Tejinder Virdee were present to congratulate the team and join in a celebration, complete with champagne and fruit tarts.

"This is a very exciting time for physics," said Virdee. "The LHC is poised to take us to a new level of understanding of our Universe."

Only the silicon pixel detector remains to be installed in the cavern, but the experiment has several months of connecting and testing CMS before the detector will be ready to take data. As the start-up of the LHC nears, there is a mixture of excitement and anxiety as pressure mounts to finish construction.

-- Katherine McAlpine, U.S. Large Hadron Collider Communications katie.mcalpine@cern.ch

Editor's Note: This research is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. The present NSF grant is for five years, with $16 million for the two year period thus far.

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.