| Compared to its Spartan predecessor, the station would house its occupants in unprecedented comfort and would contain a library and recreation center, science spaces, single-room berths for up to 23 persons, a galley, a post office, a photographic darkroom and a meeting space. There would also be room under the arches for a dispensary, biomedical facilities, vehicle repair and maintenance shops, diesel generators, a storage space for the helium used in weather balloons, and even a small gymnasium.

The buildings were heated, but the domed enclosure was not. It was vented at the top to release heat that could cause snow to form into dangerously heavy ice.

U.S. Navy Seabees began during the 1970-71 austral summer, working 10 hours a day, seven days a week. As is the case with today's construction program, they took advantage of 24-hour daylight during the fleeting summer months from October to February, when temperatures average minus 32 degrees Celsius (-25° F). Mechanical and weather delays, coupled with the crash of a Hercules aircraft, slowed work in the 1971-72 season, forcing a rescheduling of the proposed completion from January 1974 to January 1975.

During the 1972-73 season, a camp was built to house more than 100 construction workers and the dome was completed in mid-January 1973. With urgent demands for their services elsewhere on the globe, fewer Seabees were deployed during the 1973-74 season, and NSF hired a contractor, Holmes and Nervier, Inc., to make up the shortfall. In December 1974, scientists and support personnel began the move from the old station to the new one, with the move being completed by the end of the 1974-75 summer season.

On January 9, 1975, political leaders, administrators, scientists and support personnel gathered at the new Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station for a dedication ceremony.

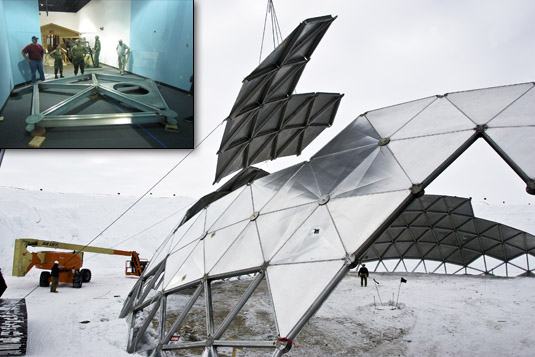

The domed station served as the U.S. research presence at the South Pole until the new station was dedicated. In the 2009-2010 Southern Hemisphere summer, the dome was finally dismantled (the interior structures under the dome having previously been taken down).

The crown of the dome and the next two rows of polygonal panels were saved for display at the Seabee Museum in Port Hueneme, Calif.

—by Peter West |

Caption & credit

Caption & credit