News Release 10-141

Extended Period of Lower Solar Activity Linked to Changes in Sun's Conveyor Belt

Results shed light on factors controlling the timing of solar cycles

The sun goes through cycles of activity lasting approximately 11 years.

August 12, 2010

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

A new analysis of the unusually long solar cycle that ended in 2008 suggests that one reason for the long cycle could be a stretching of the sun's conveyor belt, a current of plasma that circulates between the sun's equator and its poles.

The sun goes through cycles lasting approximately 11 years that include phases with increased magnetic activity, more sunspots, and more solar flares, and phases with less activity.

The level of activity on the sun can affect navigation and communications systems on Earth.

The results of this study should help scientists better understand the factors controlling the timing of solar cycles and could lead to better predictions.

The study was conducted by Mausumi Dikpati, Peter Gilman, and Giuliana de Toma, all scientists in the High Altitude Observatory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo., and by Roger Ulrich at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The results appeared on July 30 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), NCAR's sponsor, and by NASA.

"Understanding and predicting the solar cycle allows us to better prepare for coming space weather effects and, equally importantly, enables us to make more accurate decadal predictions of global climate change," says Richard Behnke of NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences.

The occurrence of solar cycles has been reconstructed going back in time about 300 years.

Puzzlingly, solar cycle 23, the one that ended in 2008, lasted longer than previous cycles, with a prolonged phase of low activity that scientists had difficulty explaining.

The new analysis suggests that one reason for the long cycle could be changes in the sun's conveyor belt.

Just as Earth's global ocean circulation transports water and heat around the planet, the sun has a conveyor belt in which plasma flows along the surface toward the poles, sinks, and returns toward the equator, transporting magnetic flux along the way.

In their paper, Dikpati, Gilman, and de Toma use simulations to model how the solar plasma conveyor belt affects the solar cycle.

The authors find that the longer conveyor belt and slower return flow could have caused the longer duration of cycle 23.

The team's computer model, known as the Predictive Flux-transport Dynamo Model, simulates the evolution of magnetic fields in the outer third of the sun's interior (the solar convection zone).

It provides a physical basis for projecting the nature of upcoming solar cycles from the properties of previous cycles, as opposed to statistical models that emphasize correlations between cycles.

In 2004, the model successfully predicted that cycle 23 would last longer than usual.

"The key for explaining the long duration of cycle 23 with our dynamo model is the observation of an unusually long conveyor belt during this cycle," Dikpati says. "Conveyor belt theory indicates that shorter belts, such as observed in cycle 22, should be more common in the sun."

Recent measurements gathered and analyzed by Ulrich and colleagues show that in solar cycle 23, the poleward flow extended all the way to the poles, while in previous solar solar cycles the flow turned back toward the equator at about 60 degrees latitude.

As a result of mass conservation, the return flow was slower in cycle 23 than in previous cycles.

According to Dikpati, the duration of a solar cycle is probably determined by the strength of the sun's meridional flow.

The combination of this flow and the lifting and twisting of magnetic fields near the bottom of the convection zone generates the observed symmetry of the sun's global field with respect to the solar equator.

"This study highlights the importance of monitoring and improving measurement of the sun's meridional circulation," Ulrich says. "In order to improve predictions of the solar cycle, we need a strong effort to understand large-scale patterns of solar plasma motion."

-NSF-

-

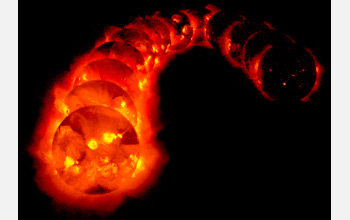

A model of magnetic flux below the Sun's surface during the solar cycle that ended in 2008.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

David Hosansky, NCAR, (303) 497-8611, email: hosansky@ucar.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov