News Release 08-128

The Lightness of Electrons in a Twisting Metal Crystal

Watching a crystal of bismuth metal in a powerful magnetic field, researchers discover new states of electrons that behave like light

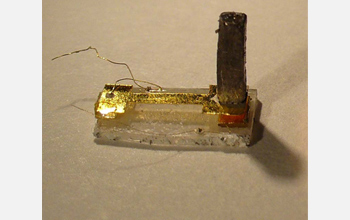

This torque cantilever is used to measure magnetic property of bismuth in intense magnetic fields.

July 25, 2008

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

A team of researchers, at Princeton University's Materials Research Science and Engineering Center and from the Universities of Michigan and Florida, has observed electrons moving through a crystal of bismuth metal behaving like light.

This discovery, supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and detailed in today's edition of the journal Science, could lead to new kinds of electronic devices.

Electrons, or the particles of electricity, fly through space like tiny baseballs. Alternatively, when an electron speeds between a crystal's periodic arrangement of atoms it behaves very differently. The fundamental equations that describe its motion in the crystal are very different from those of a free-flying baseball. For example, in bismuth, the fundamental equations of electron motion resemble those that describe the behavior of light. Although the electrons whirl about the crystal slower than at the speed of light, the electrons behave as if they are without mass like photons, the tiniest unit of light.

Over a decade ago, theoretical physicists supported by NSF studied electrons confined to artificial layered structures made of semiconductors--the stuff of which transistors are made of. They predicted that new kinds of electronic matter governed by the rules of quantum mechanics would emerge from the electrons in different layers coordinating their motions. Scientists hypothesized that bismuth crystals should also exhibit analogous electronic states.

The Princeton group, led by physics professor N. Phuan Ong, fixed a crystal of bismuth onto a flexing beam, or cantilever, and then placed this apparatus in a high magnetic field created at the NSF National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which can generate magnetic fields that are more than a million times stronger than the earth's faint magnetic field.

Under such enormous magnetic fields, the cantilever twists. The way it twists tells the Princeton researchers about the subtle new kind of matter in the bismuth crystal.

In a single crystal of bismuth, electrons are often confined to three valleys in a complex abstract landscape that scientists use to represent an electron's energy in the crystalline structure. Through careful study of the twisting cantilever, they observed a transformation from a state where the electrons prefer to occupy only one valley to a state in which the electrons share their time among all the valleys in a dance choreographed by the fundamental rules of quantum mechanics.

"This is exciting because this was predicted but never shown before, and it may eventually lead to new paradigms in computing and electronics,"said Thomas Rieker, NSF program director for materials research center.

With this work, the theory of electrodynamics suggests a rich landscape of electronic states of semiconductors, and the Princeton researchers are continuing their adventure. Someday, these newly discovered electronic states of matter may enable powerful new electronic devices that exploit the principles of quantum mechanics to compute and communicate. For now we can marvel at the subtle beauty of nature that lives in a universe of electrons that lies beneath the shiny skin of a metal crystal.

-NSF-

-

The Princeton team's research findings appear in the July 25, 2008 edition of Science.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Dana W. Cruikshank, NSF, (703) 292-8070, email: dcruiksh@nsf.gov

Program Contacts

Thomas P. Rieker, NSF, (703) 292-4914, email: trieker@nsf.gov

Related Websites

Princeton University's Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials (PRISM): http://prism.princeton.edu/faculty_direc.html

NSF's Division of Materials Research (DMR): http://www.nsf.gov/div/index.jsp?div=DMR

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov