News Release 08-042

"Nanominerals" Influence Earth Systems from Ocean to Atmosphere to Biosphere

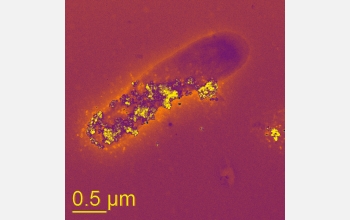

A bacteria cell living in a no-oxygen environment "breathes" using mineral nanoparticles.

March 20, 2008

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

The ubiquity of tiny particles of minerals--mineral nanoparticles--in oceans and rivers, atmosphere and soils, and in living cells are providing scientists with new ways of understanding Earth's workings. Our planet's physical, chemical, and biological processes are influenced or driven by the properties of these minerals.

So states a team of researchers from seven universities in a paper published in this week's issue of the journal Science: "Nanominerals, Mineral Nanoparticles, and Earth Systems."

The way in which these infinitesimally small minerals influence Earth's systems is more complex than previously thought, the scientists say. Their work is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

"This is an excellent summary of the relevance of natural nanoparticles in the Earth system," said Enriqueta Barrera, program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "It shows that there is much to be learned about the role of nanominerals, and points to the need for future research."

Minerals have an enormous range of physical and chemical properties due to a wide range of composition and structure, including particle size. Each mineral has a set of specific physical and chemical properties. Nanominerals, however, have one critical difference: a range of physical and chemical properties, depending on their size and shape.

"This difference changes our view of the diversity and complexity of minerals, and how they influence Earth systems," said Michael Hochella of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, Va.

The role of nanominerals is far-reaching, said Hochella. Nanominerals are widely distributed throughout the atmosphere, oceans, surface and underground waters, and soils, and in most living organisms, even within proteins.

Nanoparticles play an important role in the lives of ocean-dwelling phytoplankton, for example, which remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Phytoplankton growth is limited by iron availability. Iron in the ocean is composed of nanocolloids, nanominerals, and mineral nanoparticles, supplied by rivers, glaciers and deposition from the atmosphere. Nanoscale reactions resulting in the formation of phytoplankton biominerals, such as calcium carbonate, are important influences on oceanic and global carbon cycling.

On land, nanometer-scale hematite catalyzes the oxidation of manganese, resulting in the rapid formation of minerals that absorb heavy metals in water and soils. The rate of oxidation is increased when nanoparticles are present.

Conversely, harmful heavy metals may disperse widely, courtesy of nanominerals. In research at the Clark Fork River Superfund Complex in Montana, Hochella discovered a nanomineral involved in the movement of lead, arsenic, copper, and zinc through hundred of miles of Clark River drainage basin.

Nanominerals can also move radioactive substances. Research at one of the most contaminated nuclear sites in the world, a nuclear waste reprocessing plant in Mayak, Russian, has shown that plutonium travels in local groundwater, carried by mineral nanoparticles.

In the atmosphere, mineral nanoparticles impact heating and cooling. Such particles act as water droplet growth centers, which lead to cloud formation. The size and density of droplets influences solar radiation and cloud longevity, which in turn influence average global temperatures.

"The biogeochemical and ecological impact of natural and synthetic nanomaterials is one of the fastest growing areas of research, with not only vital scientific, but also large environmental, economic, and political consequences," the authors conclude.

In addition to Hochella, authors of the paper are Steven Lower of Ohio State University, and Patricia Maurice of the University of Notre Dame; along with R. Lee Penn of the University of Minnesota; Nita Sahai of the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Donald Sparks of the University of Delaware; and Benjamin Twining of the University of South Carolina.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

Related Websites

NSF Directorate for Geosciences: http://www.nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=GEO

NSF Directorate for Biological Sciences: http://www.nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=BIO

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov