News Release 07-147

Scientists Estimate Mercury Emissions from U.S. Forest Fires

Fires and other blazes emit 30 percent as much mercury as industrial sources

Forest fires in Alaska and California release a significant amount of mercury into the environment.

October 17, 2007

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

Forest fires and other blazes in the United States release about 30 percent as much mercury as the nation's industrial sources, according to a new study by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)in Boulder, Colo.

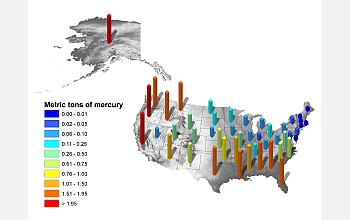

Fires in Alaska, California, Oregon, Louisiana and Florida emit particularly large quantities of the toxic metal, and the Southeast emits more than any other region, according to the study.

The scientists estimate that fires in the continental United States and Alaska release about 44 metric tons of mercury into the atmosphere every year.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), NCAR's principal sponsor, as well as by the Electric Power Research Institute and the Environmental Protection Agency.

"It's important to understand the movement of mercury through the environment," said Cliff Jacobs of NSF's atmospheric sciences division. "This study offers new insights, and points to the need for additional research to reduce uncertainty and improve our understanding of the chemical and physical processes at work."

It is the first study to estimate the amount of mercury emissions for each state, based on a new computer model developed at NCAR. The authors caution that their estimates for the nation and for each state are preliminary, and are subject to a 50 percent margin of error.

The study, "Mercury Emission Estimates from Fires: An Initial Inventory for the United States," is published online today in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Mercury does not originate in fires. Instead, it comes from industrial and natural sources and often settles into soil and plant matter.

Intense fires then release the mercury back into the atmosphere, where it poses a new danger because it can reach sensitive waterways and other areas.

"What we are seeing is that mercury from other sources is being deposited into the soil and then being released back into the atmosphere, where it can travel far downwind and contaminate watersheds and fragile ecosystems," said NCAR scientist Christine Wiedinmyer, one of the study's co-authors. "It's important for federal and state officials to have this type of information and to know where mercury is coming from so they can better protect public health and the environment."

Mercury is a toxin that can threaten human health and ecosystems.

Depending on its form, it can travel long distances in the atmosphere before returning to Earth through precipitation or dry deposition. It is particularly dangerous if it winds up in waterways, because it can transform into methylmercury and move up the aquatic food chain while becoming increasingly concentrated. The Environmental Protection Agency warns pregnant women and young children against consuming some types of fish and shellfish because of mercury levels.

To estimate the emissions, Wiedinmyer and NCAR scientist Hans Friedli, who co-authored the article, used satellite observations of fires, aircraft and ground-based measurements of mercury, and a new computer model of fire emissions that Wiedinmyer created. They focused on a five-year period from 2002 to 2006 and examined every state except Hawaii, where they lacked detailed data.

The paper warns that its estimates are subject to a 50 percent margin of error due to imprecise information about both the exact size of fires and the amount of mercury emitted by each fire. The estimates for the nation and each state are midpoints; Alaska's emissions, for example, could be anywhere from 6.3 to 18.8 tons, but 12.5 is the midpoint.

"These are initial estimates, but they clearly point to fires in certain states emitting particularly high amounts of mercury," Wiedinmyer says.

Alaska and California, which experienced vast wildfires from 2002 to 2006, released more mercury than other states. Alaska's annual emissions over the five-year period were estimated at about 12.5 metric tons, while California averaged 3.4 tons. They were followed by Oregon (2.5 tons), Louisiana (1.95) and Florida (1.89).

The authors also quantified emissions by regions, as defined by the National Interagency Fire Center. The Southeast, a region that encompasses 13 states and includes border states such as Kentucky and Oklahoma, emitted 14.4 tons per year--the most of any of the NIFC regions. In addition to Louisiana and Florida, three other Southern states ranked in the top ten: Georgia, Texas, and Alabama.

In contrast, states in the Midwest and Great Lakes emitted comparatively little mercury from fires. However, they could potentially be affected by emissions from western wildfires.

The emissions varied widely by season and year, depending on the extent of wildfires and prescribed burns. Western states in general had far higher emissions in the summer and early fall, when wildfires are more prevalent. In the Southeast, however, emissions typically peaked in the spring and fall, which may have reflected prescribed burning practices in the region.

The annual average of 44 tons for fires in the United States and Alaska compares to a total of about 108 tons that is released from industrial sources each year, such as power plants, incinerators, boilers, and mines. Mercury also comes from natural sources, including volcanoes and ocean vents.

One of the next steps for the researchers will be to examine how much mercury is deposited on nearby downwind areas, compared to how much mercury travels around much of the hemisphere. Most of the mercury in wildfire emissions is in gaseous form, traveling thousands of miles before coming down in small amounts in rain or snow. But about 15 percent of the mercury is associated with airborne particles, such as soot, some of which may fall to Earth near the fire.

"We would like to determine the risk of mercury exposure for residents who live downwind of large-scale fires," Friedli says.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

David Hosansky, UCAR/NCAR, (303) 497-8611, email: hosansky@ucar.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov