News Release 07-113

Moray Eels Are Uniquely Equipped to Pack Big Prey Into Their Narrow Bodies

Two sets of jaws capture and move prey to throat for swallowing

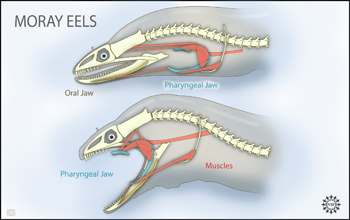

Moray eels have two sets of jaws--the oral jaws and the pharyngeal jaws.

September 5, 2007

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

How do long, slender snake-like creatures manage to stuff large, struggling prey into their narrow mouths and down their throats without using paws or claws? A new study reveals that the slender, snake-like moray eel--which may reach up to about nine feet in length--captures and consumes its prey (usually large fish, octopuses and squid) with a unique strategy that involves using two sets of jaws.

According to the study, the moray eel starts feeding by seizing its prey in the jaws of its oral cavity. This set of jaws is armed with sharp, piercing teeth that curve backwards, pointing towards the eel's throat. So structured, these teeth are specially designed to help prevent prey from backing out of the eel's mouth, much like spike-strips in parking lots help prevent cars from backing out of entrance ramps.

Once prey is secured in the eel's oral jaws, a second set of toothy jaws (known as the pharyngeal jaws) located behind the eel's skull lunges forward, advancing along almost the full length of its skull, to snatch and deliver the prey to the eel's esophagus for swallowing.

An article describing the moray eel feeding study, which was partially funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), appears in the September 6 edition of Nature. The article identifies the moray eel as the only known vertebrate to use a second set of jaws to both restrain and transport prey. Rita Mehta, a researcher at the University of California at Davis and the article's lead author, describes the eel's feeding method as "an amazing innovation for the feeding behavior of fishes."

About 30,000 fish species besides the moray eel have a second set of jaws in their throat region. But as far as we know, such jaws have only limited mobility and so only grind or crush prey; they cannot provide the essential functions provided by the moray eel's jaws.

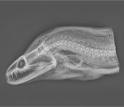

Mehta documented the moray eel's unique feeding method by using high-speed digital video equipment to record the split-second movements of feeding laboratory eels, analyzing X-ray and other images and conducting anatomical dissections.

Unlike the moray eel, most fish capture and move prey into their throats by using suction. For example, some fish rapidly expand their mouths and thereby draw in water and associated food. Others overtake prey with their open mouths or grab prey in their jaws, but then create suction to move the prey from their mouths to their esophagus. But moray eels have little ability to generate suction through their mouths, Mehta found.

More than 200 species of moray eels dwell in tropical waters worldwide. Reclusive and secretive, moray eels are most frequently observed in coral reefs, with their heads poking out of holes in rocks or coral structures. Serving as top predators in coral reefs, they may have evolved their unique feeding method to enable them to hunt large prey in confined spaces, where they cannot expand their heads to create suction.

Mehta points out that, like moray eels, snakes must also fit large food items through a relatively narrow mouth into a long, thin body. But snakes solved the problem by separating the left and right sides of their jaw while eating; they hold onto the food with one side while they work the other side of the mouth round it. Snakes thereby "jaw walk over their prey," says Mehta.

"Moray eels and snakes are not related," says Mary Chamberlin, an NSF program director. "So this study provides an excellent example of convergent evolution--where similar functions evolve independently in unrelated organisms."

Mehta said that she is now investigating how the moray eel evolved its extraordinary jaws and working to identify the maximum size of the moray eel's prey. "Eels are an amazingly diverse and bizarre group of fishes, and not very well known," said Peter C. Wainwright of the University of California, Davis, who is a co-investigator of the study.

In addition to receiving NSF support, the new eel study also received support from the American Association of University Women.

-NSF-

-

Moray eels live in confined spaces in coral reefs.

Credit and Larger Version -

A moray eel eating a piece of squid.

Credit and Larger Version -

X-ray of an eel.

Credit and Larger Version -

View Video

A moray eel eating a fish.

Credit and Larger Version -

View Video

A moray eel eats a piece of squid.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Lily Whiteman, NSF, 703-292-8310, email: lwhitema@nsf.gov

Andy Fell, University of California, Davis, 530-752-4533, email: ahfell@ucdavis.edu

Program Contacts

Mary Chamberlin, NSF, 703-292-8413, email: mchamber@nsf.gov

Principal Investigators

Rita Mehta, University of California, Davis, 530-752-6784, email: rsmehta@ucdavis.edu

Co-Investigators

Peter Wainwright, University of California, Davis, 530-752-6782, email: pcwainwright@ucdavis.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov