News Release 05-147

Climate Model Links Warmer Temperatures to Permian Extinction

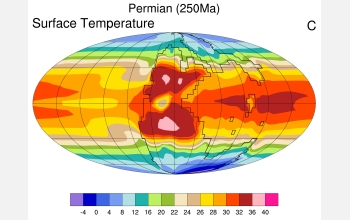

The CCSM image shows temperatures in degrees Celsius at the time of the Permian extinction.

August 24, 2005

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo., have created a computer simulation showing Earth's climate in unprecedented detail at the time of the greatest mass extinction in history.

The work gives support to a theory that an abrupt and dramatic rise in atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide triggered the massive die-off 251 million years ago. The research appears in the Sept. issue of the journal Geology.

"The results demonstrate how rapidly rising temperatures in the atmosphere can affect ocean circulation, cutting off oxygen to lower depths and extinguishing most life," says NCAR scientist and lead author, Jeffrey Kiehl.

Kiehl and co-author Christine Shields focused on the dramatic events at the end of the Permian Era, when an estimated 90 to 95 percent of all marine species, as well as about 70 percent of all terrestrial species, became extinct.

At the time of the event, higher-latitude temperatures were 18°F to 54°F (10°C to 30°C) warmer than today, and extensive volcanic activity had released large amounts of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere over a 700,000-year period.

To solve the puzzle of how those conditions may have affected climate and life around the globe, the researchers turned to the Community Climate System Model (CCSM). The model can integrate changes in atmospheric temperatures with ocean temperatures and currents. Research teams had previously studied the Permian extinction with more limited computer models that focused on only a single component of Earth's climate system, such as the ocean.

"These results demonstrate the importance of treating Earth's climate as a system involving physical, chemical and biological processes in the atmosphere, oceans and land surface, all interacting," said Jay Fein, director of the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s climate dynamics program, which funded the research. "Other studies have reached similar conclusions. What's new is the application of a detailed version of one of the world's premier climate system models, the CCSM, to understanding how rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide affected conditions in the world's oceans and on its land surfaces enough to trigger a massive extinction hundreds of millions of years ago."

The CCSM indicated that ocean temperatures warmed significantly at higher latitudes because of rising atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. The warmer temperatures reached a depth of about 10,000 feet (4,000 meters), interfering with the normal circulation process in which colder surface water descends, taking oxygen and nutrients deep into the ocean.

As a result, ocean waters became stratified with little oxygen, proving deadly to marine life. Because marine organisms were no longer removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, that, in turn, accelerated warming temperatures.

"The implication of our study is that elevated [carbon dioxide] is sufficient to lead to inhospitable conditions for marine life and excessively high temperatures over land would contribute to the demise of terrestrial life," the authors conclude.

The CCSM's simulations showed that ocean circulation was even more stagnant than previously thought. In addition, the research demonstrated the extent to which computer models can successfully simulate past climate events. The CCSM appeared to correctly capture key details of the late Permian, including higher levels of ocean salinity and high latitude sea-surface temperatures that paleontologists believe were 14°F (8°C) warmer than present.

The modeling presented unique challenges because of limited data and significant geographic differences between the Permian and present-day Earth. The researchers had to estimate such variables as the chemical composition of the atmosphere, the amount of sunlight reflected by Earth's surface back into the atmosphere, and the movement of heat and salinity in the oceans at a time when all the continents were consolidated into the giant land mass known as Pangaea.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl L. Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

Anatta , NCAR, (303) 497-8604, email: anatta@ucar.edu

Related Websites

UCAR/NCAR: www.ucar.edu

GeoSystems: www.geosystems.org

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov