Multimedia Gallery

Bubble plumes suggest warmer ocean may release frozen methane

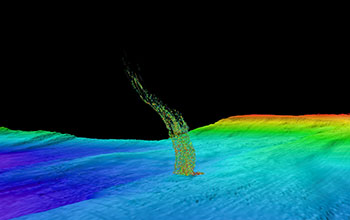

A sonar image of bubbles rising from the seafloor off the Washington coast. The base of the column is one-third of a mile (515 meters) deep and the top of the plume is at 1/10 of a mile (180 meters) depth. Research found that frozen pockets of methane "ice" transition from a dormant solid to a powerful greenhouse gas a third of a mile below the surface, in a dark ocean in areas with little marine life.

More about this image

A study by the University of Washington (UW) suggests that subsurface warming could be causing more methane gas to bubble up off the Washington and Oregon coasts. Researchers found that of 168 bubble plumes observed within the past decade, a disproportionate number were seen at a critical depth for the stability of methane hydrates. Fourteen of these plumes were located at the transition depth -- more plumes per unit area than on surrounding parts of the Washington and Oregon seafloor.

Paul Johnson, a UW professor of oceanography, says "We see an unusually high number of bubble plumes at the depth where methane hydrate would decompose if seawater has warmed. So it is not likely to be just emitted from the sediments; this appears to be coming from the decomposition of methane that has been frozen for thousands of years."

Normally, if methane bubbles rise to the surface, they enter the atmosphere and act as a powerful greenhouse gas. But most of the deep-sea methane appears to be consumed during the journey up, where marine microbes convert it into carbon dioxide, producing lower-oxygen, more-acidic conditions in the deeper offshore water, which eventually wells up along the coast and surges into coastal waterways.

Johnson says current environmental changes in Washington and Oregon are already impacting local biology and fisheries, and these changes would be amplified by the further release of methane. He says destabilization of seafloor slopes where frozen methane acts as the glue that holds the steep sediment slopes in place is another potential consequence.

The research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation.

To learn more, see the UW news story Bubble plumes off Washington, Oregon suggest warmer ocean may be releasing frozen methane. (Date image taken: 2014; date originally posted to NSF Multimedia Gallery: Jan. 28, 2016)

Credit: Brendan Philip, University of Washington

See other images like this on your iPhone or iPad download NSF Science Zone on the Apple App Store.

Images and other media in the National Science Foundation Multimedia Gallery are available for use in print and electronic material by NSF employees, members of the media, university staff, teachers and the general public. All media in the gallery are intended for personal, educational and nonprofit/non-commercial use only.

Images credited to the National Science Foundation, a federal agency, are in the public domain. The images were created by employees of the United States Government as part of their official duties or prepared by contractors as "works for hire" for NSF. You may freely use NSF-credited images and, at your discretion, credit NSF with a "Courtesy: National Science Foundation" notation.

Additional information about general usage can be found in Conditions.

Also Available:

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (1.9 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.