Do girls like math? The answer matters

This is a test: Where are the highest proportions of women working in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM): in affluent industrialized countries, or in less affluent, less economically developed countries?

The answer may surprise you. Mathematical and technical occupations and degree programs are considerably more male-dominated in rich, reputably gender-egalitarian societies like the U.S., than they are in poorer, more gender-traditional ones.

Countries such as Iran, Romania and Malaysia are among the countries where women earn the largest share of science degrees; and in Indonesia, women earn nearly half of all engineering degrees.

Maria Charles, with funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), has been investigating this seeming paradox by studying differences between girls' and boys' attitudes toward math and math-related careers. Charles is Professor and Chair of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and area director for Sex and Gender research at UCSB's Broom Center for Demography. She specializes in the international comparative study of social inequalities, with particular attention to cross-national differences in women's economic, education and family roles.

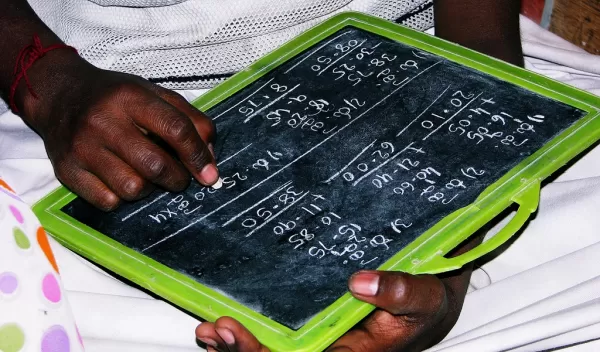

In a research study published last year, Charles and collaborators Erin Cech, Bridget Harr, and Alexandra Hendley compared adolescents' responses to questions about whether they liked math and would like a math-related job. They used data drawn from surveys of 8th-grade boys and girls in 53 countries and territories between 2003 and 2011.

Findings of the study:

The gender gap in attitudes toward mathematics and mathematically-related jobs is significantly larger in advanced industrial societies. Girls like math less, relative to boys, in more affluent societies. This is true even controlling for individual mathematical ability, social class background, curricular difficulty, and a host of other factors.

Why might this be?

Cross-societal differences in the "attitudinal gender gap," says Charles, partly reflect different cultural beliefs about gender and about the nature and purpose of educational and occupational pursuits. In societies with broad-based material security and highly individualistic cultures, students are encouraged to follow their passions and choose career paths that will allow them to express their "true selves." Self-realization through education and work is a culturally legitimate goal. But understandings of who we are, what we will enjoy doing, and what we will be good at are influenced by culture, including widely-held beliefs about gender difference.

According to Charles, most people don't know in advance what sort of work they will most enjoy and be good at. This often means that boys and girls draw upon cultural gender stereotypes to guide their choices: "What do people like me enjoy and what are they good at?" This may lead girls to occupations and degree programs that they believe will be aligned with culturally feminine "selves."

In a previous NSF-funded study, Maria Charles and Karen Bradley, dubbed this phenomenon "indulging our gendered selves."

"Maybe gender gets expressed in a way less tied to work in less affluent societies," says Charles. "When material well-being is more of a concern, people might not expect to self-realize through a job. They may do so in other ways."

Adolescence is a crucial time for students to imagine a range of possibilities for their future study and work--and a time when these choices are often narrowed unnecessarily. Research suggests that adolescents are the group most reluctant to transgress cultural gender norms and most influenced by stereotypes about what they're good at and what they will enjoy.

Says Charles, "Most people don't really know what they're going to like until they do it."

Existing patterns of occupational sex segregation and the gender stereotypes surrounding many STEM fields insure that many girls and women never consider these fields. Scientific and technical work is often portrayed as solitary and isolated, populated by nerds and geeks--certainly not where culturally feminine aptitudes and affinities will be appreciated or put to good use.

"There's a lot of work being done to improve the climate in workplaces--but if girls don't have any interest in those fields and opt out of math during secondary school, it isn't enough to improve the climate."

There are things that we can do to address a global shortage of labor for STEM work.

Increasing the pool of labor available for STEM work will depend in part on increasing girls' and women's interest in STEM. This in turn will depend on gradual erosion of two kinds of cultural stereotype: Those that depict women as innately suited for a narrow range of female-labeled work, and those that depict scientific and technical work as uncreative, solitary and fundamentally masculine.

Charles also notes that more years of math could be required for high-school graduation in the United States. In some states, students can graduate with a very low level of proficiency. This doesn't give girls or boys a chance to really find out whether they're good at math or whether they like it.

"More training in math helps students keep their options open," says Charles. "Even if you don't know what you want to do, it's important to keep in mind that some interdisciplinary graduate programs, not necessarily even in STEM, require math through calculus. If you opt out of math early, it's difficult to go back and get what you need."

In a follow-up study, Charles finds that the attitudinal gender gap among eighth graders grows and becomes closer to that in the U.S. and Europe as developing and transitional societies attain higher levels of economic development. This has consequences for the global STEM workforce.

"It's a problem in terms of finding enough labor to fill these positions," says Charles, "And the U.S. and other countries have been dealing with the shortage partly by importing labor from less affluent countries, which may slow the economic development of those societies."

"Maria Charles' findings in this area are both surprising and terribly important," said NSF Program Director Jolene Jesse. "As we work to engage students of all backgrounds in STEM, this research is valuable to educators, policymakers and families."

More details on Charles' study and her papers are online. A follow-up study is planned for later this year.

Math Awareness Month 2015 begins tomorrow. Its theme is "Math Drives Careers."